In 2015, The Atlantic ran an article asking What Good is Twitter?, after the magazine's metrics revealed that only a fraction of@TheAtlantic followers click on just a few of the links to articles.

Perhaps he should have titled it “Twitter Doesn’t Drive Link Traffic” or something else less universal, because Twitter has been very, very good for us at the Business Innovation Factory. The reason? Our primary aim for Twitter is not to drive traffic to our site, although we certainly hope that happens. Our primary aim for Twitter is community. We don't currently have an independent online platform for our community, so Twitter is still where we gather.

We use Twitter to participate in actual conversations with our own community and with other interested (and interesting) people. We use it to start conversations about our events, to find and join existing conversations, and to start and nurture conversations that grow our community and sometimes evolve into communities of their own.

We use Twitter to connect with people around our analog events, particularly our annual Collaborative Innovation Summit, which features a robust tweetstream active months before and months after our Summit. but also smaller events, such as the one featured in this case study.

Case Study

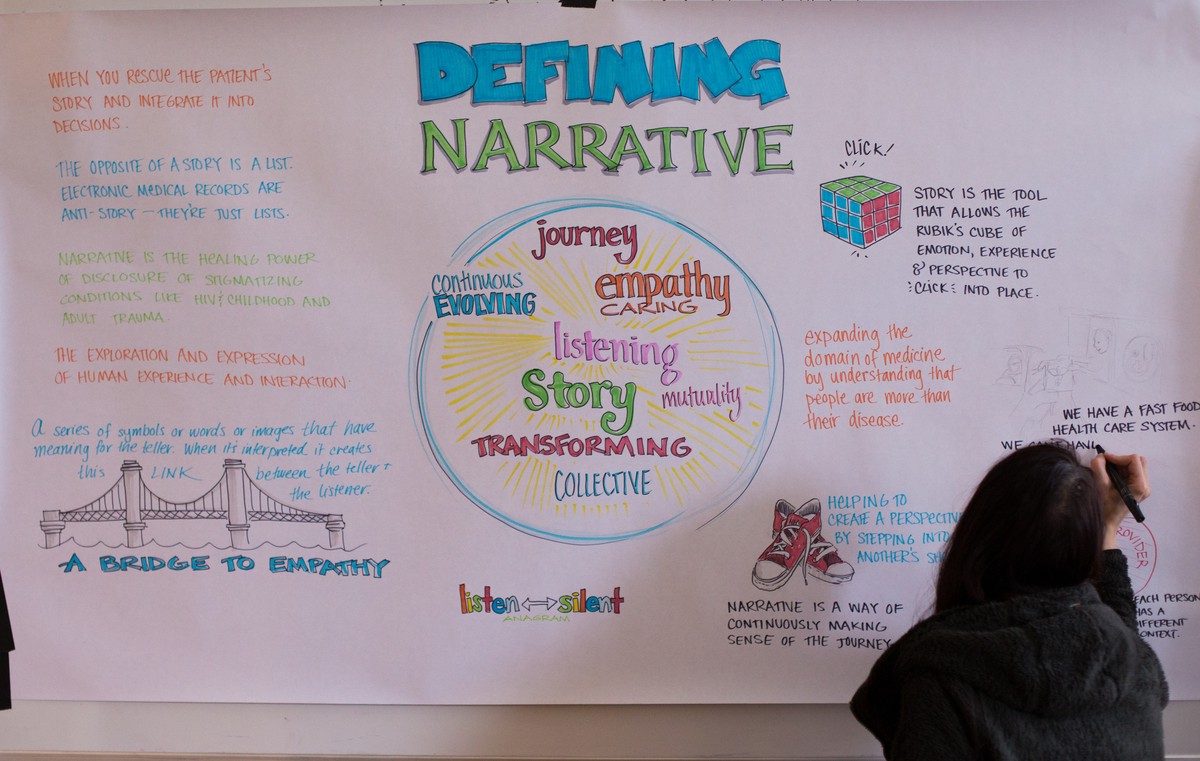

The event: a two-day Participatory Design Studio held in Feb. 2015, in conjunction with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The design studio was part of a project to imagine, design and build a playbook for healthcare narrative. Called the Power of Narrative, the project’s aim was to explore the use of narrative in healthcare with those who use it and/or those who see the need for it — doctors, nurses, artists, writers, patient advocates, patients and more.

Design the Experience

As the project began, we decided to consciously find (or create, if necessary) the place on Twitter where the conversation on this subject was happening, or could happen. Not finding an existing hashtag that would encompass all the stakeholders, we created #hcnarrative as a “home base” for the conversation.

No one can actually own a hashtag, but we registered the hashtag and the description of what it was for on Symplur, a site that monitors and collects information on healthcare-related hashtags.

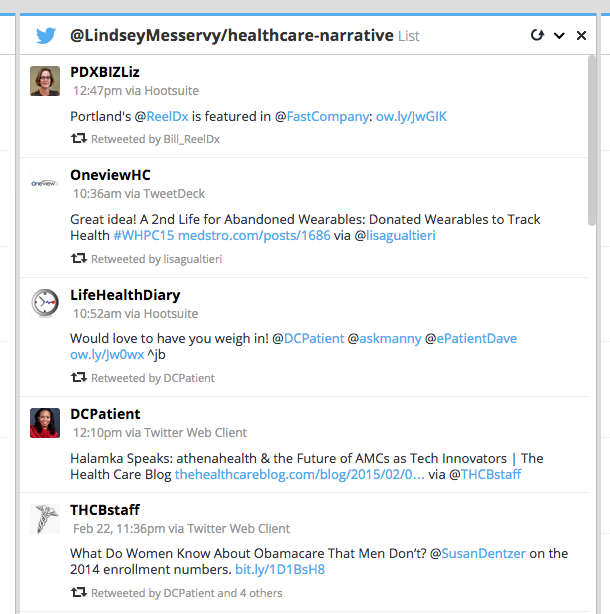

Next, we made a Twitter list of the 30 or so people who had been invited to the design studio and also had Twitter accounts. This allowed us to more easily converse with our participants before, during, and after the event.

Work Out Loud

We participated in the conversation ourselves prior to and during the event — essentially, working out loud and showing our work. These tweets came from our main @TheBIF account and our Patient Experience Lab account (@BIFpxl), as well as the accounts of BIF staffers @Renee_Hopkins, @LindseyMesservy, @leighcappello, @skap5 and @elithechef.

On the days of the event, we encouraged tweeters in the group to live-tweet the proceedings. Some heavy tweeters like @ReginaHolliday and @AfternoonNapper would have done it anyway, regardless of what we said! We set up a large monitor so the participants could see the Twitter stream in real-time (we use the free site Twitterfall for this).

As the two-day event progressed, tweets flew into #hcnarrative. From the beginning, a number of people outside the room were following, commenting, asking questions and in general participating. As a small nonprofit, we don't have the budget for expensive software to monitor participation. So, other than observing the tweetstream during the event, how do we know how many were following and who they were?

Create and Share Artifacts

Twitter no longer allows users to download the results of a hashtag stream, and @Storify doesn't present all the tweets (unless they've added that feature since I last checked). So we contracted before the event with software engineer John Lewis (@JohnWLewis) to provide a transcript of the tweetstream, from the time starting just before and continuing to just after the event. Examining the PDF transcript showed that while we had 25 tweeters in the room, 108 different Twitter accounts were represented in the tweetstream during the time of the event.

We made the document available to participants through the project page, and one BIF team member wrote a blog post using some of the tweets. Also, @BethTonerRN from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation created a Twitter-based story of the event using Storify.

The tweetstream archives joined the other artifacts from the event — notes from exercises, visual notes, photos, video. That makes for a rich store of information and insights available to the BIF team members who created the playbook. Much of this information is publicly available on the project page. And the conversation in the hashtag remained strong post-event, was still being used to discuss BIF and this project as of Dec. 2015, 10 months after the actual event.

So, what is Twitter really good for? For us, it's good for conversations — finding them, starting them and nurturing them. These conversations enrich and grow our community— and sometimes grow into a community of their own.